slovenščina

slovenščina

hrvatski

hrvatski

English

English

Why do we watch content that gets on our nerves?

Hatewatching draws us in, boosts our dopamine, and wastes our time. But it’s also the first step toward online hate. Let’s not allow haters to shape the tone of our posts.

The text summarizes the lecture “How To (Re)Move Haters”, presented by Branka Bizjak Zabukovec at the Dan_d event.

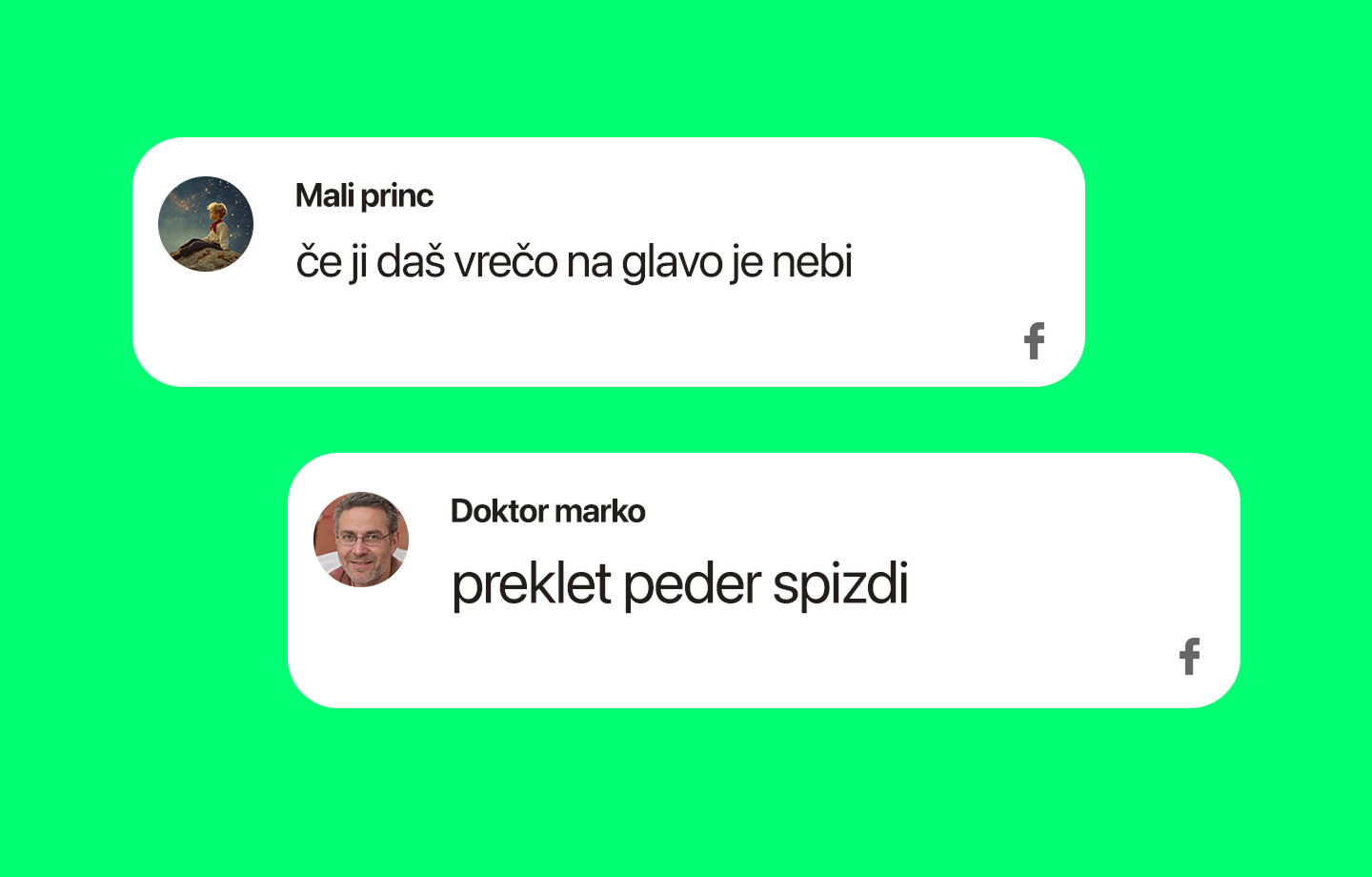

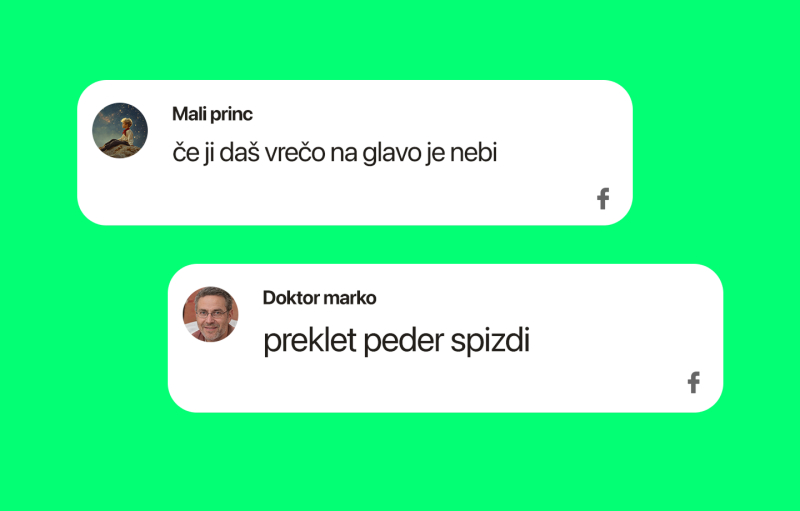

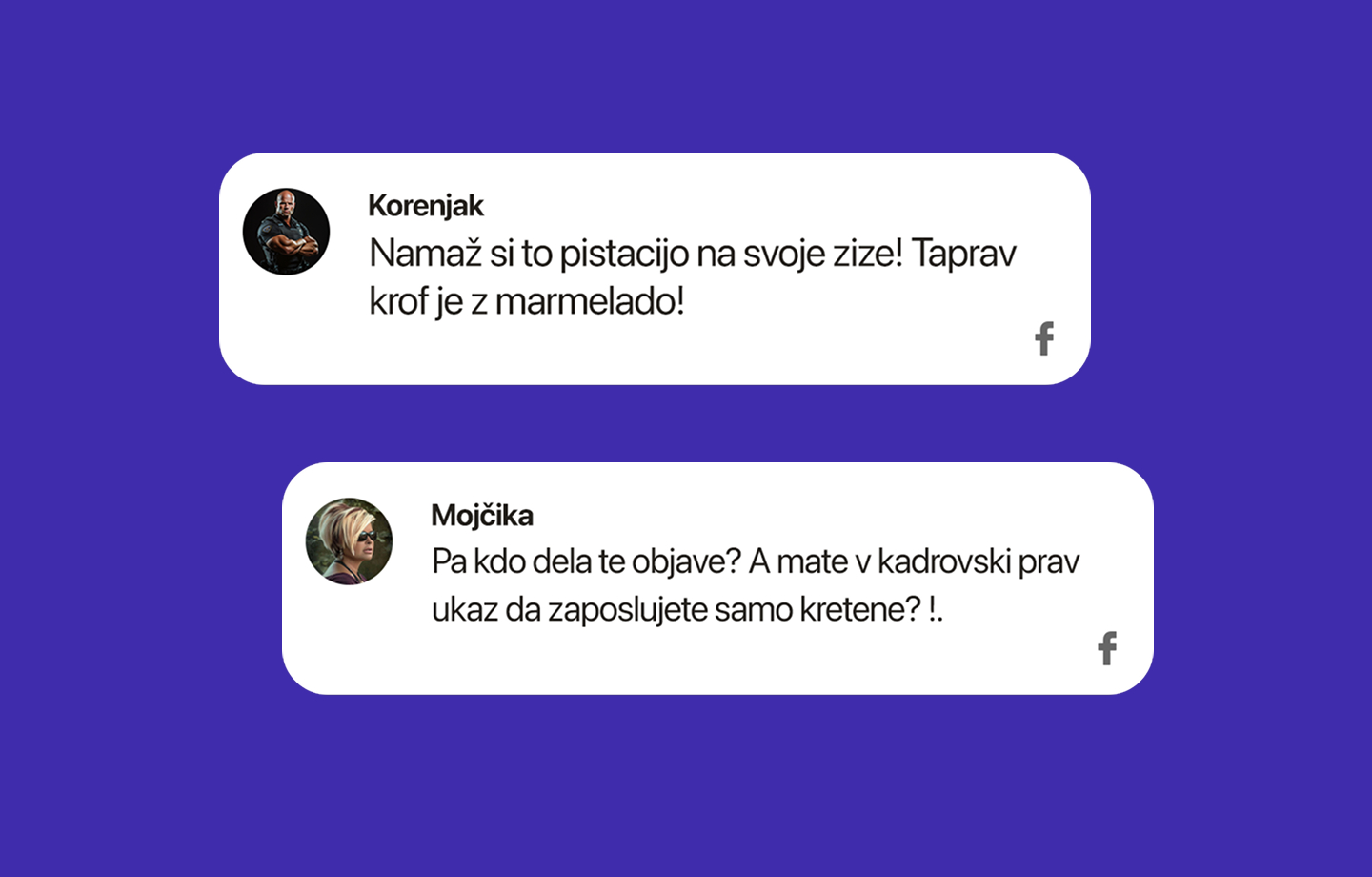

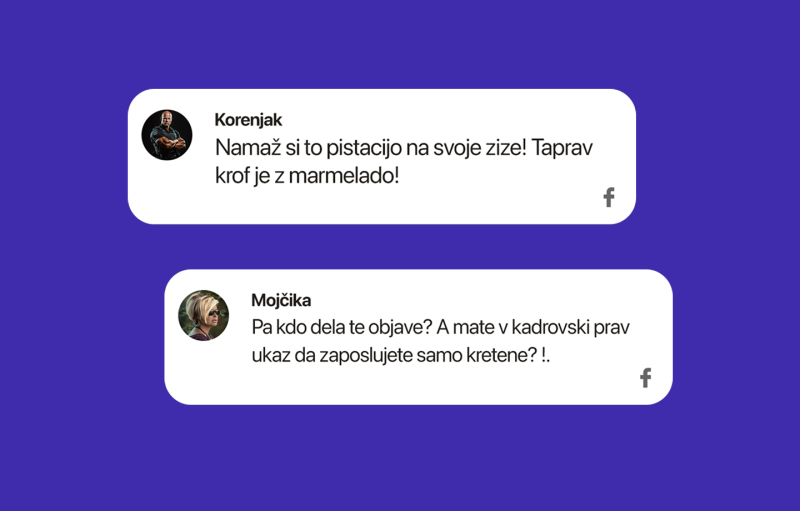

How did you react to the comments on the post? Did you roll your eyes, smile, or maybe even chuckle? Let’s admit it—if you’re not the social media manager who has to deal with this under the post, it’s all kind of funny in a weird way. Reading such ridiculous comments can give us a sort of voyeuristic pleasure.

We know it’s not exactly right, and we cringe. But still, it’s like a car accident you drive past. You don’t want to look. You know seeing the wrecked cars and possible injuries won’t do you any good. Yet, you glance anyway.

If there’s a truly witty hater comment, you might even “like” it.

Watching content we disagree with, that annoys us—whether it’s comments, shows, or influencers—is hatewatching.

And hatewatching is the first step toward hating, as well as highly “caloric” fuel for haters.

Haters are social media users who leave unconstructive, critical comments under people’s or brands’ posts (at best), and often their comments are insulting, rude, degrading, or even hostile.

Have you ever wondered why haters hate? Most of the time, the reason doesn’t lie with you. In fact, it’s usually not about disliking you, your posts, or your brand. The reasons are often elsewhere. Let’s look at the four most obvious ones.

Seeking approval

Haters hate to gain approval and recognition from like-minded people. A hater writes a comment and then eagerly waits for likes. Every like they get means: “They notice me, they agree with me, I’m right, I matter.” This triggers a dopamine boost.

Need for belonging

Hatred unites more than kindness. The reason is that negative emotions—like anger, frustration, and hostility—are often felt more intensely than positive ones, and that intensity connects us. In English, we call this bonding over negativity. People are more likely to form connections with others if they share a common dislike or hatred toward a topic or group. This gives a strong sense of belonging: “us versus them.”

Artificial superiority

Haters attack your posts because, in the Facebook, TikTok, or X universe, they want to signal that they are better than you—whether it’s in grammar, design, writing, cooking, furniture-making… anything. They always know best. If you’re not sure what I mean, check out the Facebook group “Society for the Protection of the Semi-Literate.” It’s made up entirely of people who have never misplaced a comma in their lives.

Personal frustrations

People who are dissatisfied with multiple aspects of their lives—frustrated, in simple terms—are more likely to find satisfaction in putting others down. A 2024 study titled Social Media Stars vs. the Ordinary Me showed, for example, that followers with lower levels of self-acceptance—those who felt a big gap between who and what they were and who and what they wanted to be—reacted far more negatively to influencer posts.

Even though we know that haters’ hostility usually has nothing to do with us, it’s still not good to let their comments pile up under our posts. Why?

Humans have always operated on the principle of social proof. When we don’t know how to react in a certain situation, we look around, see what others are doing, and then adjust our behavior accordingly.

Imagine a neutral user sees our post and can’t decide what to think about it. Should they see it as bold, funny, special, different…? Since they’re unsure, they’ll click on the comments and see what others think about the post. And they’ll form their own opinion based on those comments. If those comments come from haters, their reaction to the post is likely to be negative as well.

As a social media manager, you probably don’t want haters dictating how your followers feel about your posts.

That’s why haters are not okay. The sentiment of the first comments under a post often shapes the sentiment of the rest of the comments. So, what can we do to prevent them from being hateful?

Three tactics:

1. Make good use of the “hide” button

Hide the comment. This means only the hater (who won’t know it’s hidden) and you can see it. No one else can see it, so it won’t negatively influence anyone.

2. Enlist friends’ help

For posts that you think might attract haters, make sure positive or at least neutral comments appear under it as soon as possible. How? Ask a few friends to leave a comment.

3. Don’t let them intimidate you

One hater doesn’t ruin everything—ignore them and keep doing good work.

With a bit of cynicism, we can say that brands aren’t actually the favorite targets of haters. The preferred targets are usually influencers.

In the study “Too Lucky to Be a Victim”, the authors explain that influencers are “easier to hate” for the following reasons:

They are not seen as weak or vulnerable.

A large part of the public believes they deserve criticism because of their visibility.

Harassers don’t feel responsible, as it’s seen as a collective action.

Some even believe that harassment is a “fair punishment” for influencers’ inappropriate behavior.

The wider public often normalizes and justifies online abuse toward influencers.

In the image above, we can see some more hateful comments that influencers have received.

What do these comments tell us about the influencers?

Absolutely nothing!

And what do they tell us about the haters?

At the very least, that they spent a considerable amount of time watching content created by someone they clearly dislike. And that is hatewatching.

How many times have we all caught ourselves watching content, an influencer, or a reality show where the performers annoy us… and yet we keep watching? That, too, is hatewatching.

There’s a simple chemistry behind it.

In the first second we see someone we don’t like, our cortisol levels rise slightly. That’s what wakes us up, makes us alert, and grabs our attention—which is harder and harder to do with the sheer volume of content out there.

Next, when our suspicion is confirmed—that this person is really annoying, either because of what they say or do, or just who they are—our dopamine spikes. “Yes! I knew they were clueless.” Our expectations are met, and dopamine rises.

Immediately after comes serotonin—because I’ve realized they’re foolish, which means I’m smart, and I feel good about myself.

But!

Our brains want more. Always more! One story is never enough. And suddenly we find ourselves spending time on things we dislike and that bring us NO benefit, sacrificing something we’ll never get back: our priceless time.

We’d be better off spending it on people and things that make us better versions of ourselves!